Author: Yesica Costucica

Executive Summary: The mega-cap technology stocks that have led the current stock rally will undoubtedly be major beneficiaries of the AI trend. However, the benefits of this new technology will expand well beyond these companies.

During our last quarterly call, we said that dominant players in the AI industry like Microsoft, Alphabet, and Nvidia would be big beneficiaries of the development of this new technology. Boy, are we glad we said that! Since then, these stocks have led the markets higher. Now we have to look beyond mega-cap tech, towards which other companies could also be potential beneficiaries.

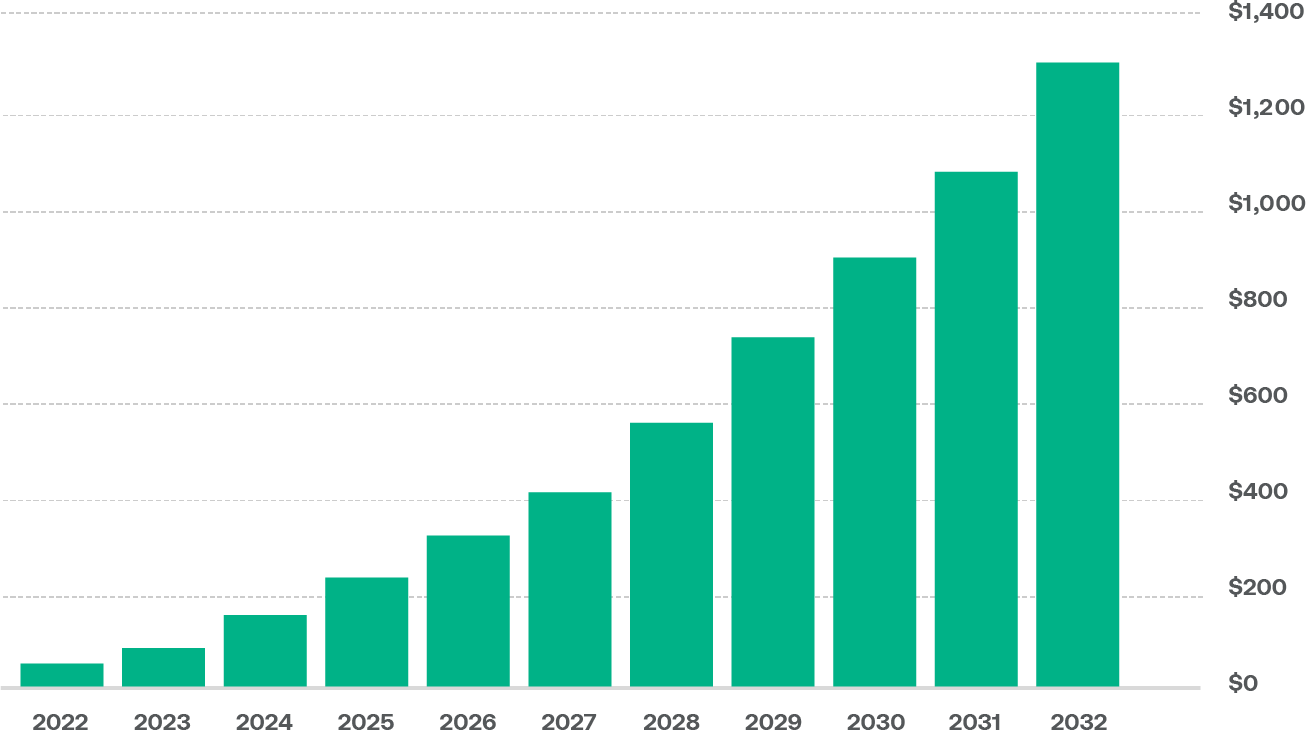

A year ago, artificial intelligence appeared to be a promising technology far in the future. Few people had heard of it, and even fewer had been exposed to it. Fast-froward a year, and artificial intelligence is something very real. Most of us have heard about AI by now. Whether we were introduced to it through the media, a friend, or even personal use of Chat GPT, we can all envision the revolutionary implications that artificial intelligence could have on our everyday lives. Much like with the birth of the internet, a nascent technology such as AI has created a large amount of appetite from investors looking to get exposure to what portends to be a promising bounty. As we can see on the chart on the next page, Bloomberg estimates that Generative AI could lead to approximately $1.3 trillion in revenues by 2032, spread across several technology industries including “hardware, software, services, ads, and gaming centers, growing at an annual compound rate of roughly 42%…” (Mandeep Singh, Nishant Chintala, and Anurag Rana, Bloomberg, 6/5/23). Investors have clearly expressed their views as to which companies would benefit from the AI boom. Stocks such as Microsoft (MSFT), Alphabet (GOOGL), Meta (META), Amazon (AMZN) and Nvidia (NVDA) have helped propel stock markets higher this year. But so far, the markets appear to be pricing in the idea that only a handful of large-cap technology stocks will be the big beneficiaries from the AI boom. Nvidia alone rose 190% in the first six months of this year, reaching a market cap slightly over $1 trillion. To put things in perspective, the market cap of Bitcoin is approximately $600 billion. Said another way, all the Bitcoin in the market would only purchase 60% of Nvidia. Using the same logic, considering that Microsoft’s market cap is close to $2.5 trillion, the same amount of Bitcoin would only buy about a quarter of Microsoft.

There is little doubt that the dominant players in the AI space such as the companies mentioned above have a lot to gain. Companies engaged in the actual development of the technology will undoubtedly be big beneficiaries of its application. However, the markets are almost behaving like these will be the only companies that will benefit. But what about the second-derivative companies, those beyond mega-cap tech? What about those companies that will be the users of AI or provide services ancillary to the technology?

Artificial intelligence networks can be operated on a large-scale basis, with networks running hyperscale models, or on a smaller scale basis running off cloud-based networks. Nvidia is the dominant player providing data processing equipment for large-scale models powering AI for big end users such as data centers. However, when it comes to cloud-based or ethernet networks, like the ones that will most likely be used to power AI in smaller units such as your smartphone, Nvidia has competition. Companies such as Broadcom (AVGO) and Cisco Systems (CSCO) also offer ethernet solutions that compete with Nvidia, and their stocks trade at less than half of the valuation of their larger rival. As we said before, we have no doubt that first movers like Nvidia will be winners in the AI era. However, let’s remember that this company is predominantly a hardware manufacturer, making the equipment that enables AI. What about the companies that create and use software to power and benefit from artificial intelligence?

During a recent interview, Cathie Wood, manager of the famous ARK family of disruptive technology funds, stipulated that “…for every $1 of AI-related hardware that Nvidia sells, software firms will eventually generate $8 of revenue.” (Cathie Wood, Bloomberg, 6/7/23). As we can see on the next chart, software spending on AI is expected to grow from approximately $5 billion to close to $280 billion by 2032. In fact, AI as a percentage of total software spending is expected to grow from less than 1% currently, to 12% or potentially higher over the next ten years. This increased level of spending on AI is expected to come from a number of industries, such as healthcare, cyber security, software development, robotics, and automation.

Projected Revenues for the Technology Sector from AI (in billions of USD)

Source: Bloomberg Intelligence, IDC, Insigneo, as of 6/1/23

The healthcare industry is one that is set to potentially be revolutionized by the adoption of artificial intelligence. Robots might not replace doctors anytime soon, but they might help make their jobs easier. Overtime, AI is expected to simplify some tasks for clinicians, such as gathering patient information and providing diagnoses and recommendations for simple ailments. This could potentially decrease the need for patients to visit medical clinics and emergency rooms, decreasing the load on the system and shortening appointment wait times. AI could also potentially affect pharmaceutical companies, taking on some of the simpler drug development and manufacturing processes.

Cyber security is another industry that will certainly be affected by artificial intelligence in more than one way. With new technologies come new groups of people trying to exploit them, so it is only a matter of time before hackers try to find ways to use AI for nefarious purposes. We are already hearing stories of AI being used to create fake pictures of events that did not happen or replicate human voices in an attempt to fool a person on the other end of a call. On one hand, artificial intelligence could fill the need for cybersecurity professionals, or at the very least, become an assistant, freeing them to do more specialized tasks. On the other hand, cyber security will be in high demand to protect the valuable networks and software required to operate this new technology. The global market for AI-related cyber security spending could surpass $100 billion over the next decade. Companies like Fortinet (FTNT), Palo Alto Networks (PANW), Okta (OKTA) and ZScaler (ZS) could be potential winners in this space over the long term.

Along the same lines, software development is likely to be simplified, with faster turn-around times, as artificial intelligence is used to read, write, and analyze code. Companies in data aggregation and analytics end markets such as Palantir Technologies (PLTR), Salesforce (CRM), and Snowflake (SNOW) are set to reap meaningful benefits, as they use AI to extract value out of raw data, along side their larger peers in the industry. In fact, symbiotic relationships are likely to flourish between many companies in this segment of the market.

The robotics, defense, and automation industries will also prove to be clear beneficiaries of artificial intelligence. We are already seeing defense companies such as Boeing (BA), Lockheed Martin (LMT), and Northrop Grumman (NOC) begin to test weapon systems based off their own drone platforms that could operate with artificial intelligence. These systems could potentially operate on their own, or at the very least provide a “virtual co-pilot” for the human in charge of the platform. Industrial companies such as Rockwell Automation (ROK), Johnson Controls (JCI), General Electric (GE), and Siemens (SIE GY) are already using artificial intelligence to promote machine learning and create tools and processes to exponentially boost production. The use of goods created by these companies permeates throughout a broad base of industries in the global economy, ranging from the processing of food and drinks to aircraft and auto manufacturing.

Projected Spending on AI Software (in billions of USD)

Source: Bloomberg Intelligence, IDC, Insigneo, as of 6/1/23

“A myriad of factors, including infrastructure and regulation could impact the adoption speed of AI. Most regions in the world currently lack the proper infrastructure to maximize the benefits of this new technology.”

More broadly and perhaps most significantly, the exponential boost to global production capacity over the coming decades is set to have a meaningful impact on productivity growth across the world. Some estimate that the impact of artificial intelligence on global productivity will be akin to China’s joining of the World Trade Organization in 2001 or the internet boom at the beginning of the millennium. These moves lowered labor costs and increased the interdependency of global manufacturing, eventually increasing productivity and driving overall prices lower. However, it took time for these dynamics to have a meaningful impact on global productivity. It is estimated that the internet boom took between 10-15 years to meaningfully increase per capita GDP in most countries around the globe. This is better than the 50+ years that it took the Industrial Revolution to achieve a similar outcome. It will most likely take the AI revolution considerably less time to achieve a meaningful, permanent move in global productivity. Some say that this number could be between 5-10 years, some say it could be less.

A myriad of factors, including infrastructure and regulation could impact the adoption speed of AI. Most regions in the world currently lack the proper infrastructure to maximize the benefits of this new technology. On the regulatory front, we are already seeing regulation take shape in Europe. Earlier this month, government officials in the United States debated the implications of AI on the global arena and how to regulate and mitigate some of its risks.

We have no doubt that artificial intelligence is here to stay and that it will have a meaningful impact on our lives, most likely in a shorter period than the internet boom did. It is important to keep in mind though, that however long it takes, it will probably not be overnight, as some in the market appear to believe. The mega-cap technology stocks that have led the current stock rally will undoubtedly be major beneficiaries of the AI trend. However, the benefits of this new technology will expand well beyond these companies. ■

Mauricio Viaud – Insigneo’s Senior Investment Strategist and Portfolio Manager.

After the pandemic, the term “nearshoring” became popular in the media. Given the potential implications of this phenomenon on the Latin American region, it is worth exploring it in more detail. Forbes describes nearshoring as a “tactic that allows companies to move their operations to the closest country with a qualified workforce and reduced cost of living without the time difference.” (Maritza Diaz, Forbes, 2021). In essence, nearshoring is a form of offshoring, but with different goals in mind.

Offshoring became popular in the 1980’s as many companies relocated their production facilities to countries such as China, India, and Bangladesh, as relatively lower labor costs reduced manufacturing expenses and increased profit margins. Eventually, this trend grew to encompass the relocation of service facilities. However, offshoring presented two main problems, namely geographic distances, and time zone differentials. Vastly different time zones meant that colleagues in the same company would have to work very different hours, with some working through the night to provide the support or services needed by their teammates or end clients. Most impactful were the geographic distances that had to be traversed in order to ship materials and finished products halfway around the world. This dynamic became painfully evident during the Covid-19 Pandemic.

As we can all remember, the world came to a grinding halt during the Pandemic. Most people were working from home or within limited hours. That also meant companies were producing less, and airplanes and ships were transporting less goods. This dynamic put severe pressures on the world’s supply chains of goods and services. As the global economy began to eventually reopen and goods were slowly being produced again, production lines were sometimes forced to stop due to lack of supplies or raw materials required to complete production. Consumers around the world had to wait months for appliances or furniture, as a product manufactured in one country could not be shipped to a different country because of lack of materials or heavy backlogs and bottlenecks in the logistic supply chains. This dynamic was most evident in the supply of semiconductor chips, the infamous “chip shortage”. These experiences made companies in the West keenly aware of their dependance on Asian suppliers, especially on China. Understandably so, this heavy dependence on China posed significant security risks, particularly for the United States. Trade wars between the United States and China had frayed commercial relations between both countries before the Pandemic began. Combined with the supply chain issues experienced in 2020-2021, these dynamics pushed the United States to seek diversification in its supply chain. This is where the concept of nearshoring emerged.

In a move to reduce its dependence on Asia, the United States has been working to bring back manufacturing and services either back to the country (reshoring), or close to it (nearshoring). Some production is being brought back to Canada; however, most of it will likely be relocated to Latin America. In the chart above, we can see the Interamerican Development Bank’s estimates for incremental exports expected to arise in the region from the nearshoring movement. The bank expects as much as $78 billion in incremental exports from the region over the short and medium term. Of this number, it expects approximately 80% to stem from the production of goods, and 20% from the production of services. The automotive, pharmaceutical, textile, and renewable energy industries are expected to see the largest gains. As is evident on the table, Mexico is expected to be the biggest beneficiary in the region, followed by Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, and Chile.

Additional Potential Exports for the Region (in billions of USD)

Source: Interamerican Development Bank, Bloomberg Linea, Insigneo, March 2023

Due to its geographic proximity to the United States, Mexico should prove to be the biggest beneficiary of nearshoring, potentially seeing incremental exports almost five times greater than the next country on the list, Brazil. In Mexico’s northern region, cities like Monterrey are already seeing a boost in the technology industry. Local universities, such as Tecnologico de Monterrey, are producing well-trained engineers capable of handling specialized, tech-oriented roles that were previously handled in Asia. Companies such as Tesla, Volkswagen, and BMW continue to expand their presence in the region. We are seeing railway companies such as Canadian Pacific expand their networks from Canada to Mexico in an effort to reduce lead times and get products to market quickly and efficiently. Banks such as Banorte are investing heavily in Mexico’s northern region to support its booming industries. The bank foresees a migration of workers from the south to the north of the country, as opportunities brought about by nearshoring create more employment. In fact, Banorte recently announced it will add 800 jobs in northern Mexico to have the capacity it needs to meet increased demand for mortgages, business loans, and general banking services. An increased need for infrastructure to support increased demand should also lead to job creation, helping the local economy. In fact, the expectation of this dynamic has helped bolster the Mexican Peso, as well as the country’s equity markets. We are even seeing the flourishing of new startup companies in the country, such as the logistics company Nowports, that are positioning themselves to benefit from nearshoring trends. Multilateral trade agreements between the United States, Mexico, and Canada should continue to facilitate increased trade between these countries.

“The nearshoring phenomenon has the potential to be a game changer for many countries in Latin American. It is up to these countries to properly embrace this dynamic”

Mexico will not be the only country to reap the benefits of nearshoring. Countries like Brazil, Argentina, and Colombia are also investing in education programs to produce a skilled workforce of engineers and other specialized roles that will enable them to meet the requirements of multinational companies. El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras are seeing an increased number of call-centers relocating to their countries. As a result of its stable financial system and friendly business policies, Uruguay is increasingly seeing the expansion of Free Trade Zones. Like Mexico, these countries share similar cultures and democratic values, as well as time zones that are, for the most part, aligned with those of the United States.

There are a few important dynamics that could pose a challenge to the full embrace of nearshoring in the region. The most important is potential political instability. Most governments in the region recognize the benefits that nearshoring could bring to their countries. However, changing political regimes, along with the regulatory changes these could entail, could give pause to companies looking to relocate their operations to the region. Onerous or ambiguous regulatory frameworks could also pose barriers to nearshoring opportunities. Most companies in the United States operate under a regulatory framework, that although sometimes cumbersome, tends to be clearly defined. Ambiguous or seemingly arbitrary frameworks could cause companies to look elsewhere for relocation opportunities. High crime rates, or the perception thereof, is also an important consideration. Companies looking to relocate operations have to send employees from other regions to the host nations. Many times, these companies will choose not to operate in areas with high crime rates to not put their existing employees in danger.

The nearshoring phenomenon has the potential to be a game changer for many countries in Latin American. It is up to these countries to properly embrace this dynamic for the good of their economies, as well as their people.

Mauricio Viaud – Insigneo’s Senior Investment Strategist and Portfolio Manager.

Latin America and Lithium are intertwined in a nascent relationship. It is estimated that out of the 89 million tons of lithium reserves in the world, as much as 60% of these are found in Latin America. The majority of these deposits, over 55% of total global deposits, lie in a region known as the “Lithium Triangle”, comprised of Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia. As we can see on the chart, approximately 24% of lithium resources lie in Bolivia, 22% in Argentina, and 11% in Chile.

Mexico, Brazil, and Peru also play into the mix, as these three countries combined represent about 4% of global resources.

Global Lithium Reserves

Source: United Nations Development Program,

U.S. Geological Survey, Insigneo, as of 2022

However, not all lithium reserves are created equal. The basic raw materials needed for the creation of lithium generally come from two sources: a mineral rock called Spodumene and a salt-based brine. As of 2020, 65% of lithium production stemmed from Spodumene, 33% from brine, and 2% from other sources. Most of the production of Spodumene is in Australia, while brine production is mostly found in the salt flats of Chile and Argentina. It is because of the resources in these flats, that the “Lithium Triangle” has the potential to have a major impact on the region. That being said, lithium can be hard and expensive to produce, particularly in regions requiring intensive mining. This could explain why certain countries, such as Mexico, are having limited success developing this industry. In a recent report by the United Nations Development Program, the UN Assistant-Secretary General and UNDP Regional Director for Latin America and the Caribbean noted that industry experts believe that “the marginal cost of producing refined lithium of both carbonate and hydroxide would range between $6,000-$8,000/ton through 2036.” (Luis Felipe Lopez-Calva, UNDP, 2022). This cost level poses significant limitations to the development of reserves in certain countries in the region. When we compare the potential reserves that could be mined, against what countries are actually producing, we can see the effects of these high costs of production. For example, as we pointed out before, Bolivia accounts for 24% of global lithium deposits, with Argentina and Chile coming in at 22% and 11%, respectively. However, data from the U.S. Geological Survey, and published by the United Nations Development Program, paint a different picture with regards to actual production. As we can see on the next chart, despite accounting for the largest amount of reserves in the world as of 2021, Bolivia accounted for 0% of global lithium production. On the other hand, accounting for only 11% of reserves, Chile accounted for 25% for global production. So, why this discrepancy?

Blessed by geography, Chile is home to the largest portion of the Atacama Desert. As a result, the country has some of the best lithium brine deposits in the world, which again due to favorable geography, can be produced at relatively lower costs than in other regions. Additionally, the country’s access to the Pacific Ocean gives it easy access to ports, from which the product can be exported to Asia. For these reasons, Albemarle and Sociedad Quimica y Minera de Chile, two of the world’s largest producers of lithium, have meaningful operations in the country. However, permitting and other regulatory constraints pose a challenge for production growth in Chile, as well as in other countries in the region.

Resource nationalism is another dynamic that we are seeing play a role in limiting lithium production in the region. Fearing the influence of other countries on their reserves, countries like Bolivia and Mexico are pushing for the creation of an OPEC-like “Lithium Cartel” to act as a group in setting prices for the product. However, this attempt to set price controls could prove to be detrimental to some countries in the region, as not all lithium reserves and their mining requirements are equal. Additionally, given the region’s fluctuating political environment, this could also add an extra layer of complexity to an already volatile pricing backdrop for the commodity. Lithium pricing is dictated by different variables across different markets. After lithium is mined from Spodumene or produced from brine, these raw materials must then be processed into lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide, the chemicals that are used to create batteries. Approximately, 65% of this processing takes place in China. As a result, pricing varies depending on the type and quality of the material, as well as the market where it is produced or processed. As we can imagine, the demand for lithium has increased over the past decade as demand for Electric Vehicles has meaningfully grown around the world. Demand has increased significantly in North America and Asia, particularly in the United States and China. As could be expected, this has driven prices of lithium through the roof. Prices for some of the key chemical components needed to produce lithium are much more expensive than they were over the last 5 years. However, over the past few months, lithium prices have retreated off their highs by as much as 20%, particularly in China. This latest drop was caused by lower end market demand in that country. In our view, prices could remain volatile over the short-term. However, the supply/demand dynamics for lithium are still favorable, and although prices could come down temporarily from elevated levels, their trend is most likely to continue to point upward over the long-term.

Lithium: Global Reserves Vs Global Production

Source: United Nations Development Program, U.S. Geological Survey, Insigneo, as of 2022

As mentioned before, most of the processing of raw lithium into finished products happens in China.

There is interest from both the United States and China to increase the amount of processing facilities in Latin America. The United States, for example, is interested in this dynamic for two reasons. First, there is the geographic advantage to having lithium mined and fully processed close to end markets at home. Companies like Albemarle already have a presence in the country, yet other companies are also making inroads, as evidenced by Tesla’s newly announced lithium processing plant in Texas. However, and likely more important, processing lithium in Latin America would eliminate the country’s dependence on China for this part of the production chain. As we can imagine, diversifying its production and processing base has meaningful implications for the United States, from a national security standpoint.

If Latin America adopts policies that will create a benign environment for lithium producers, the region could be poised to be a big beneficiary of the increased long-term demand for this product. If instead governments enact policies that make it difficult for companies to establish themselves in the region, the benefits of this natural resource could be limited. Granted, all stake holders have to derive some form of benefit from the abundance of lithium in the region. Compromise that favors everyone involved is key. ■

Mauricio Viaud – Insigneo’s Senior Investment Strategist and Portfolio Manager.

One of the most repeated lessons from this history is that scarcity leads to innovation. Incidentally, the corollary to this principle is that hubris leads to downfall – just ask Putin how his ill-advised and ill-planned invasion of Ukraine is going. Another important teaching is that political and macroeconomic systems are very complex. And people tend to focus only on the first order effects of policy and decision-making. But it is usually the second, and even third, order effects that are most important and least accounted for, the ones least priced-in by markets.

“the English went from a state of a permanent energy crisis to one of energy abundance much sooner than any other place.”

With these ideas in tow, let us take a closer look at the Industrial Revolution, one of the seminal transformative events in history. It is accurate to assert that this period was as important to humanity as the adoption of agriculture in terms of progress. So, we all know very well that the Industrial Revolution began in England during the late 18th and early 19th century. But why did it begin there and not, say, in Spain or France that had similar technological advancement? And why during that time period? Well, as promised, this thousand-year chart offers some clues. As it shows us, woodland as a percentage of land use fell continuously in England from about 1100 AD to right before the commencement of the Industrial Revolution. By deforesting their own island, the English were running out trees. And trees were very important back then because they were the main source of fuel. England, we have a problem. In response, the English began importing trees from the Baltic regions, where there was a surplus of timber. But this trade was regularly interrupted by the Danes and the Swedes. This meant that the English were constantly dealing with a major problem for any economy – fuel scarcity. Well, this energy crisis – scarcity – led to innovation: the English were the first to experiment with coal as a source of energy. Necessity is the mother of invention. It turns out that coal is a more efficient as a source of energy than timber – 26K BTUs per ton for coal versus 14K BTUs per ton for wood. Because of innovation born out of necessity, the English went from a state of a permanent energy crisis to one of energy abundance much sooner than any other place. One other feature of coal is that it is much heavier than timber. This means that the English also had to develop canals and other transportation systems that could move the coal from where it was dug up to where it could be transformed into usable fuel. Scarcity led to innovation which led to the Industrial Revolution which led to the British Empire dominating the world for over a century.

So, let us return to the present and long-term forecasting. Who could be the big winner of the next decade? No one today would say Europe. Everyone is short the Euro, short European Industrial Stocks, etc. If you have a six-month time horizon, if you are a trader, a short-term investor, then that is the probably the appropriate risk stance.

“English also had to develop canals and other transportation systems that could move the coal from where it was dug up to where it could be transformed into usable fuel.”

This chart shows Dutch natural gas from the generic futures contract prices. Since 2021, they have skyrocketed, punctuated with dramatic upward shifts every time Russia makes a major move or threatens another escalation. Europe is in the throes of a major energy crisis – largely of its own making, by the way. But if you are long-term investor, is that the appropriate stance? I would say no. Let me explain why.

Despite the fact that over the past decade European industrial companies pay a 30% to 50% premium for electricity use over their American counterparts (that cost premium today is close to 100%), their export share of global exports has remained largely in line over that same time period. That means that over the past decade, American companies have wasted their electricity cost advantage versus their European competitors by not taking market share from them. Another way to state is that higher European energy input costs have not decreased their competitiveness. Moreover, as the US exports more liquified natural gas to Europe and uses less for domestic consumption due to higher prices abroad, European and American liquified natural gas prices will converge – European gas prices will fall, and US prices will rise. This should reduce the energy advantage that US companies currently enjoy over their European counterparts. Finally, Europe leads the world in renewable energy use. 30% of European energy consumption comes from renewables versus 19% for the US and 18% for the world.

It will probably continue to innovate on renewable energy precisely because of its energy scarcity problem. It has to, it’s a matter of survival. Think about it, where is the next big breakthrough in energy likely to come from? A place where energy is abundant and cheap like the US or the Middle East? Or a place where it is scarce and expensive like Europe? Again, necessity is the mother of invention.

“30% of European energy consumption comes from renewables versus 19% for the US and 18% for the world. It will probably continue to innovate on renewable energy precisely because of its energy scarcity problem. It has to, it’s a matter of survival.”

My bet would be that it is in Europe where that breakthrough will materialize. Remember the medieval English and their problem of energy security.

As a long-term investor, how do you deploy this trade? You buy the European Industrial sector. This graph shows you the performance of European industrial companies versus their American counterparts. As you can observe, American industrial stocks have greatly outperformed over the past 12 years. The smart bet is that this trend will not continue. Either because European electricity costs will come down as the US exports more natural gas to Europe, or because Europe innovates faster and better, or both that trend should reverse. The only way this trend does not reverse is if Europe does not innovate its way out of its scarcity problem. That is a bet that goes against the grain of human history. It is not one anyone should make. For long-term investors, European industrial companies are a good bet.

Ahmed Riesgo – Insigneo’s Chief Investment Officer

Mr. Riesgo oversees all the company’s research and investment functions. This includes investment strategy, devising and implementing the firm’s global market views and asset allocation, communicating them to its clients and the public, and managing the firm’s model portfolios. In addition, he is the Chairman of the Insigneo Investment Committee.